What's happening to China's new upper-stages?

China has experienced its fourth upper-stage breakup in orbit this year.

In the last year the Long March 6A has become notorious for its second-stage breaking up in orbit. In recent weeks, it appears that the Long March 12, China’s newest launch vehicle, is also facing a debris problem.

In March the Long March 6A Y3’s second-stage suffered from a breakup releasing over sixty pieces of debris. This was followed by another breakup in July, after the vehicle’s Y7 launch, scattering an unknown number of debris. Lastly following the launch of the first eighteen Qianfan satellites, the Y21 vehicle’s second-stage catastrophically broke up into up to nine hundred potential pieces of debris. A similar event was also observed in November 2022 following the Long March 6A Y2 mission, creating over fifty pieces of debris.

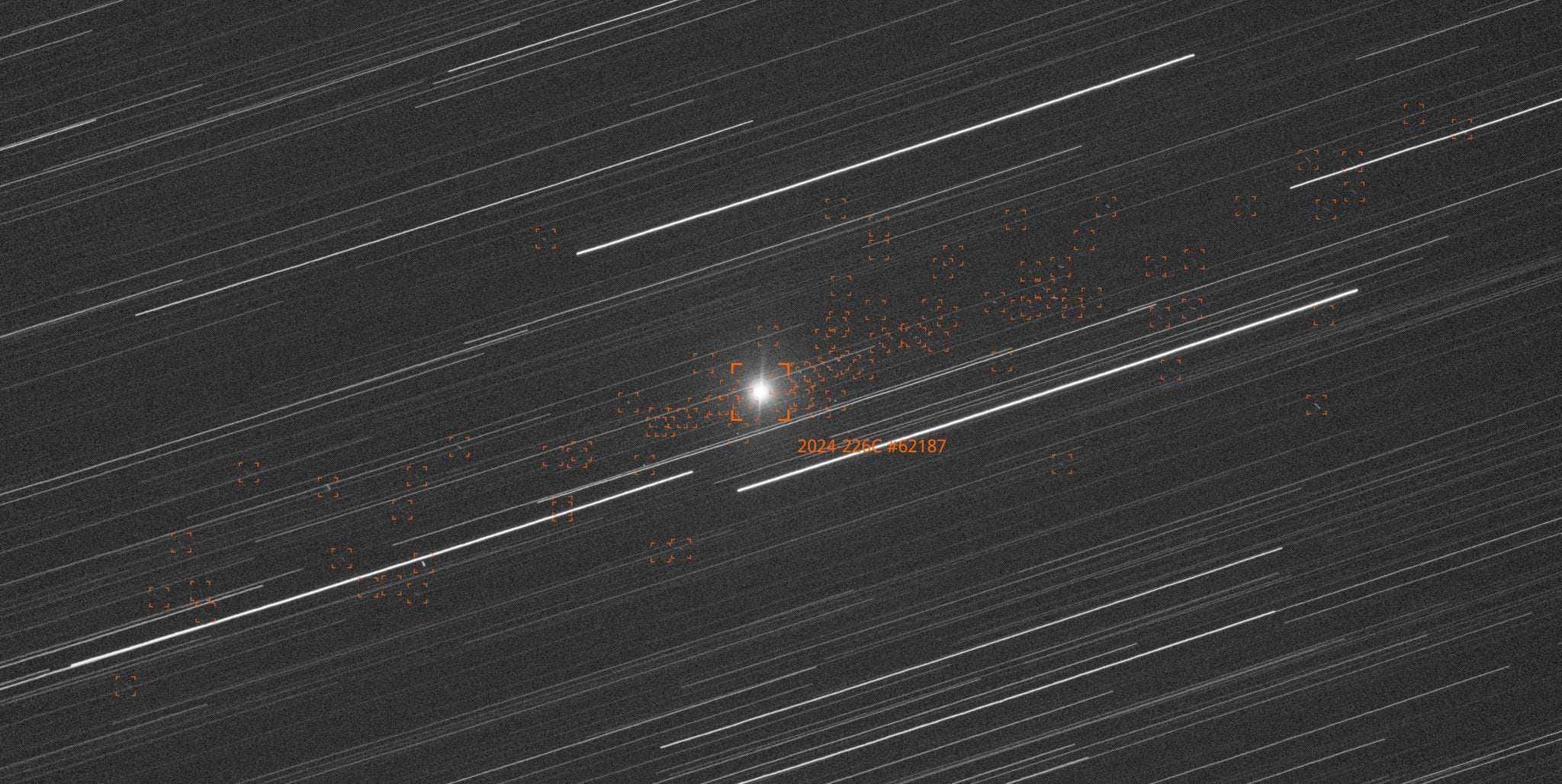

Most recently the Long March 12 Y1’s second-stage was spotted in orbit with a debris field forming around the stage in the weeks following launch, with possible debris seen fifteen hours after launch. The number of debris from this upper-stage has not yet been counted.

Two things link the problems faced by these upper-stages from China’s new generation of launch vehicles. First, both vehicles are manufactured by the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology. Second, both vehicles use the YF-115 engine.

To date the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (上海航天技术研究院) manufactures seven launch vehicles, three older generation and four newer generation: Long March 2D, Long March 4B, Long March 4C, Long March 6, Long March 6A, Long March 6C, and Long March 12. Four of these, all in the newer generation of rockets, use the YF-115 engine in the second-stage.

The Long March 6A and Long March 12’s second-stages are the largest cryogenic stages developed by the Shanghai Academy. The 6A’s second-stage is 3.35 meters in diameter and approximately 5 meters tall, with a volume of roughly 44 cubic meters. The 12’s second-stage is 3.8 meters in diameter and approximately 5.2 meters tall, with a volume of roughly 59 cubic meters. (Exact figures about these stages have not been released).

So what’s causing these rocket stages to break up? Jim Shell, a space domain awareness and orbital debris expert, wrote on LinkedIn that the problem may be related to the stages passivization process, this process aims to remove any potential internal energy. Stages using the YF-115 engine have been observed in the past venting unused propellants, the Long March 12 Y1 vehicle was also observed undergoing this process. How long these stages take to passivize is relatively unknown along with how much potential energy is removed.

Depending on the passivization process, the propellant tanks of the stage may be at different pressures along with the intertank section, which both rockets have. This pressure difference may lead to intertank pipes bursting or collapsing followed by parts of the tank, leading to the creation of debris. Some high-pressure gasses from the YF-115 engine may also head back toward the propellant tanks or cause a faulty shutdown too, creating quite energetic debris inside and around the engine.

Alternatively, China could just be incredibly unlucky and be experiencing many untrackable collision events, but I find that scenario quite unlikely.

So what can be done to prevent this issue? With the little information we know the easiest solution would be to quickly bring the stage back into the atmosphere. This could however create further problems as, depending on when a deorbit burn occurs, a potential debris field could be spread across a larger area of space. Another solution could have China employing a small fleet of debris removal satellites, a technology the country proved in early 2022 along with possibly training satellite operators in the methods to do so.