Western Press Continues Concerns over China's Mega-Constellations

Genuine concerns or performative posturing?

SpaceNews, a publication dedicated to informing Western policymakers, published a story on April 7th regarding the deployment of China’s Qianfan (千帆) and GuoWang (郭望) internet-providing mega-constellations. The story claims, based on observations by former U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. and now military consultant Jim Shell, that China will launch the majority of all “debris” in Earth orbit via the deployment of its major constellations.

To make this claim, Shell asserts, in a post beginning with “China’s mega mess on orbit”, the following:

“Late in 2024 China started launching their two "mega constellations" into low earth orbit. The [Qianfan] and [GuoWang] constellations. For both constellations, the rocket upper stages are being left in high altitude orbits -- generally with orbital lifetimes > 100 years!”

”There will be some 1000+ PRC launches over the next several years deploying these constellations. I have not yet completed the calculations but the orbital debris mass in LEO will be dominated by PRC upper stages in short order unless something changes.”

“Area/mass dependent, but 600 km is generally considered the altitude to be compliant with the legacy 25 year orbital lifetime rule.”

Shell’s analysis is based on a few flawed points and are:

China will only launch satellites for mega-constellations on the Long March 6A and Long March 8.

Current mega-constellation launches are not for initial constellation tests and are operational launches that will not change flight trajectories in the future.

Assumes that upper-stages currently on-orbit following constellation orbits are uncontrollable and unpassivised1.

Assumes that the upper-stages are untrackable.

First, China will use other rockets, including upcoming commercial ones, to launch its constellations and remain on track with its deployment plans. Space Pioneer stands a good likelihood of launching at least one batch of Qianfan satellites in 2025 should they make a second launch attempt this year, following a successful debut flight.

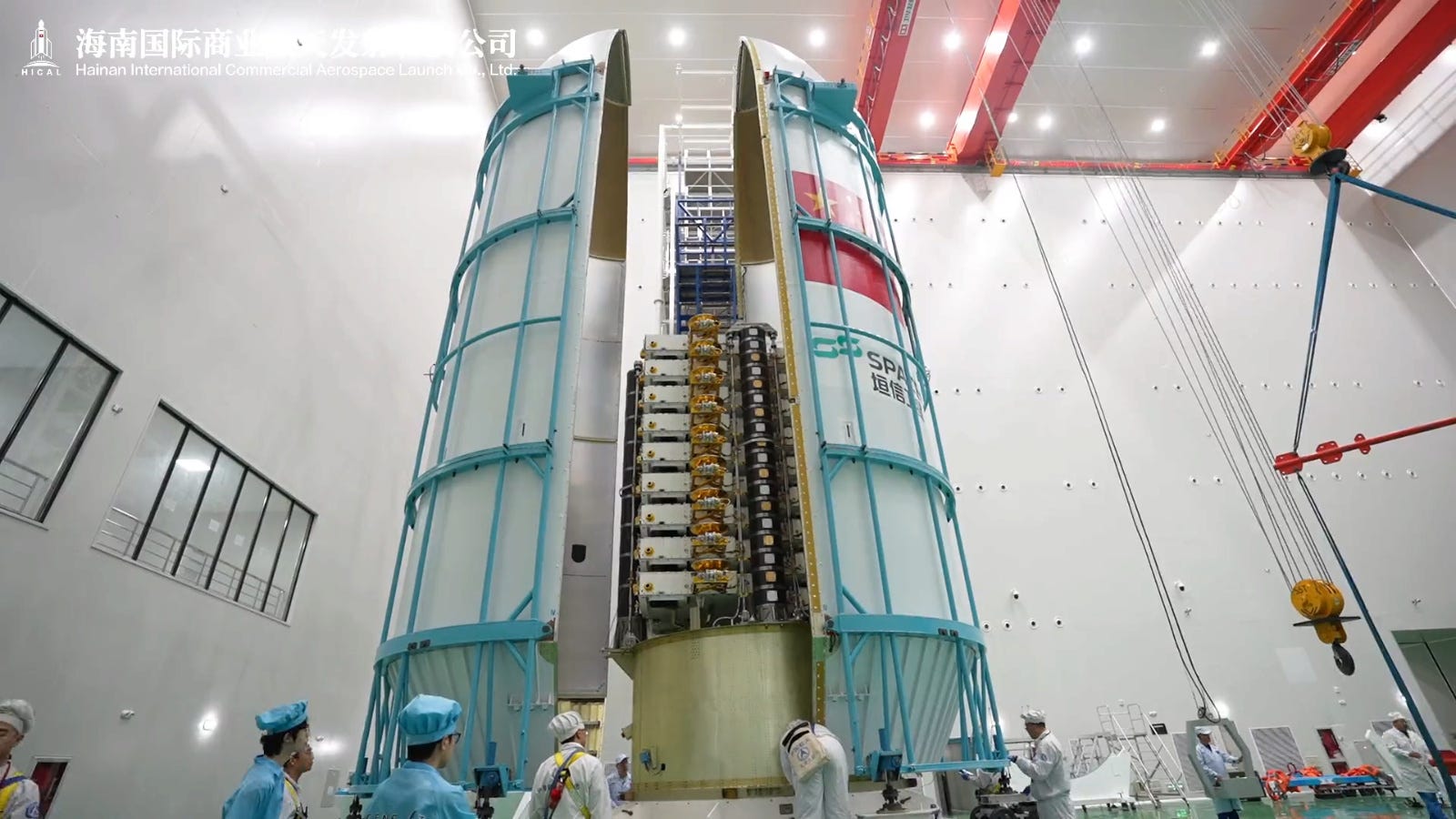

For context, Qianfan satellites are currently launching atop of the Long March 8 and Long March 6A, for which a few dozen launches have been allocated to bring the constellation up to its initial global operational capacity. The initial capacity for the constellation is around seven hundred satellites, needing up to thirty-six launches total (five have occurred), with plans to scale up to nearly fifteen thousand satellites in the 2030s.

Second, the current launches for the two constellations are tests to launch semi-mass production spacecraft. As such, current launches for the satellite groups are aiming to get as close to the 1,100-kilometer operational orbit as is performantly possible. SpaceX used to launch Falcon 9 near Starlinks operational altitudes before later switching to a lower altitude deployment, both to carry more of the newer, heavier satellites and to allow atmospheric drag to deorbit faulty spacecraft.

But why can’t China’s mega-constellation satellites be deployed lower than 800 kilometers up? Quite simply, SpaceX has deployed around six thousand Starlink satellites at altitudes of 500 kilometers and below. At this early stage of deployment, it would be irresponsible to launch the satellites into a similar orbit.

Third, despite some issues last year, China does passivate its upper-stages and de-orbit them when available. At this stage of deployment, as mentioned previously, much greater performance is needed to reach a higher orbit, reducing or removing de-orbit propellant. Before the onboard batteries run out, the vehicle is left in a stable state.

Fourth, upper-stages are quite bright when compared to satellites, thus easily trackable both from the ground and in space. This applies to stages out towards geostationary orbits too.

Additionally, the legacy twenty-five-year rule was an American standard set by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. China does have similar space debris rules, based on the UN’s Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, with similar or better standards actively being worked on.

Brightness concerns

In addition to debris situations, concerns were raised about the brightness of Qianfan satellites back in October, following the mega-constellation’s first launch. A paper released in September 2024 stated that Qianfan satellites have an observed magnitude of between 4 and 8. These observations were based off of the first batch of 18 satellites launched in August.

At those magnitudes, the satellites are visible to the naked eye on the ground, similar to Starlink trains. Ground-based observatories and the International Astronautical Union’s Centre for the Protection of Dark and Quiet Skies from Satellite Constellation Interference recommend a magnitude of 7 or below to mitigate interference.

The team behind the paper said to SpaceNews that they conducted their study to raise awareness and prompt change in the constellation. Part of the team is also a part of the International Astronautical Union’s Centre for the Protection of Dark and Quiet Skies from Satellite Constellation Interference group and refused to comment to SpaceNews if they had been in, or attempted to contact those who operate the Qianfan constellation, being Shanghai Spacesail Technologies Co Ltd.

Similar concerns were raised about SpaceX’s Starlink constellation when it began launching. According to SpaceNews, current Starlink satellites have a magnitude of 7 after launch. Direct-to-device Starlink satellites, which began launching last year, are also brighter than current Starlink satellites by a factor of 2.6 once mitigations may be applied.

Genuine concerns or performative posturing?

When based in solid fact, concerns about China’s Qianfan and GuoWang constellation should be properly considered, with risks or issues mitigated where applicable (like Starlink has had and does still have). Space debris-wise, international space law should be updated through institutions like the United Nations to mitigate space debris from any nation. Meaningfully protecting the international commons of space will take more than a strongly worded statement on how best to use it.

For example of major debris from the U.S., the breakup of Blue Origin’s New Glenn’s upper-stage out in medium Earth orbit2 or United Launch Alliance’s Centaur upper-stage (repeated several times) in a geostationary transfer orbit. There are of course the few breakups from China late last year.

To end, arguably it says something about the state of Western reporting on China as the article from SpaceNews was based upon a single social media post that self-admits to incomplete calculations, and then taking those incomplete calculations to experts for them to comment on.

The passivation of a spacecraft is the removal of any internal energy contained in the vehicle at the end of its mission or useful life. In this case, the removal of the two main fuels. (via Wikipedia on April 7th 2025)

A medium Earth orbit is any orbit between 2,000 and 35,786 kilometers in altitude.

I like that someone is posting a balanced take.

By that measure (ref to original news in the article), there are more than 500 pieces of Delta upper stage debris above 1000km - and at least 16 unpassivated but intact upper stages still lurking at those “long term” altitudes..