China on Track to Be Preeminent Space Power, U.S. Gov Suggests

A 4-hour long Senate hearing provided many repeated, and some new, insights into how the U.S. views its competition with China in space.

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission held a hearing in the U.S. Senate on April 3rd regarding China’s space program, orbital capabilities, and potential threats to American assets in space. This hearing was split into two panels, which were as follows:

Panel 1: U.S. Space Force’s Perspective on Strategic Competition with China in Space

Panel 2: Space as a Contested Domain: Expansion of China’s Military and Commercial Space Activities

The first panel had the U.S. Space Force’s Chief of Space Operations, General B. Chance Saltzman1 testify for around ninety minutes. The follow-up second panel had Blaine Curcio2 of Orbital Gateway Consulting, Victoria Samson3 from the Secure World Foundation, Brien Alkire4 of the RAND Corporation, Dave Cavossa5 from the Commercial Space Federation, and Andrew Cox6 of Fourspoke LLC testify for around one hundred minutes.

China in Space usually doesn’t cover the political activities of the United States, outside of op-eds, but I feel it is important to highlight what was said at the hearing, by the commission, with the questions put forward, and part of the testimonies.

Remarks from the Commission

Before the hearing got underway, the two Co-Chairs of the commission set the tone for the hearing overall, stating:

Commissioner Mike Kuiken: “Today we examine a critical threat, China’s rapid advancement in both its civilian and military space programs. We must understand what this means for U.S. national security, technological leadership, and global influence. What’s happening in China’s commercial and military space industry follows a similar and familiar pattern, we’ve seen it with semiconductors, with Huawei, with solar panels, with batteries, with electric cars, and with biotech. China is following its proven playbook. It is systematically building the manufacturing and R&D infrastructure to iterate rapidly, and seize dominance in space.”

“China observers routinely talk about China’s civil-military fusion. Let’s be clear-eyed China’s pursuing a whole-of-nation approach to compress decades of American and European space innovation into just a few years, positioning it to leapfrog ahead. China has fuelled its space ambitions through all of its familiar illegal and grey zone tactics, cybertheft, deceptive joint ventures, forced technology transfer, talent recruitment programs, academic espionage, lawfare, hostile takeovers, and strategic acquisitions that ultimately relocated technology to Chinese soil.”

“During our recent Made in China 2025 hearing, [unintelligible] warned that we have one thousand days to not lose in biotech. The same urgency applies to space, we have no time to waste. Losing in space would mean surrendering our military advantage, economic opportunities, and the ability to set international norms. Imagine an alternative history where America didn't lead in space, its not science fiction to say our world would look dramatically different. This, the original Sputnik moment, served as a catalyst for action. The space race with the Soviet Union defined the mid-20th century. Our competition with China in space will shape the 21st century.”

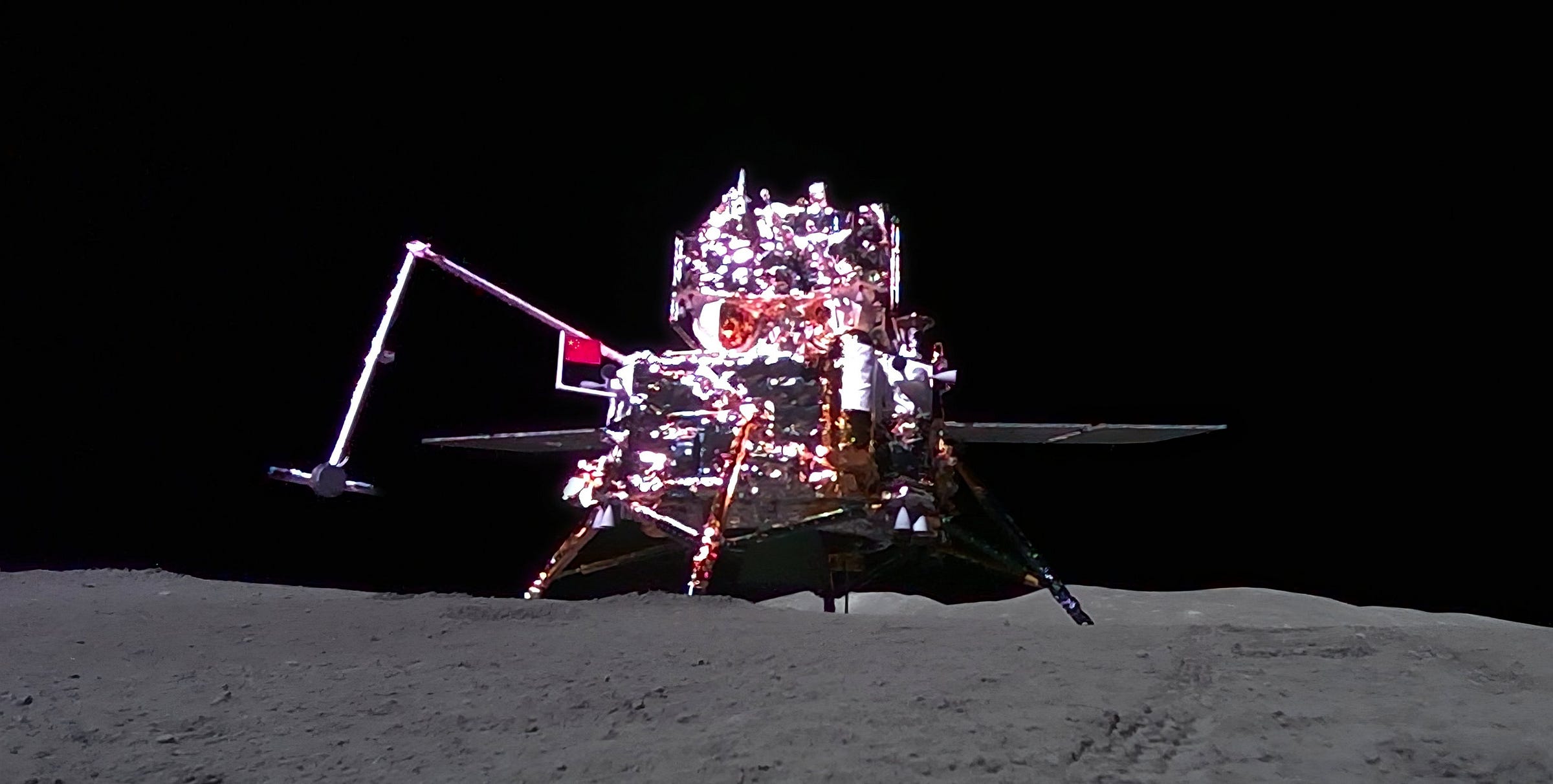

“Since the commission’s last hearing on this topic in 2019, China’s space ambitions have become achievements. Their civilian space milestones are not merely symbolic, they are calculated moves to challenge U.S. leadership. By 2030 China plans to land on the Moon and return samples from Mars, by 2035 they aim to establish an operational lunar research station, by the 2040s China plans to expand its lunar base and explore beyond Mars and Jupiter. These are not distant dreams, they are concrete steps in a strategy to cement China’s position as a global space power. China’s ambitions extend far beyond exploration, their commercial space sector is booming.”

“Once dominated by state-owned giants, China’s commercial space industry expanded after 2014. The government opened the door to private investment, a new wave of companies has surged into the market, China’s market has more than doubled from 2019 to 268 billion Dollars in 2023 and are estimated to get to 900 billion dollars by 2029. China’s companies are racing to deploy reusable launch rockets and mega-constellations, they aim to crowd out U.S. companies and dominate space in the near term. China is already deploying cutting-edge quantum satellites while the U.S. companies trail behind. Meanwhile, China’s crewed space station and ambitious lunar mission plans seek to challenge American leadership in human spaceflight as well. This is not about technological bragging rights, China’s expanding space power poses real military and economic challenges."

“The PLA’s counter-space capabilities are advancing as well, Beijing’s influence over the global space governance is growing too as a former Department of Defense leader and leading expert on space policy recently warned our space sector, the U.S. space sector, has long been an advantage for the United States. We need to keep that advantage. The United States cannot afford complacency, our technological innovation, talent development, and military readiness are being tested.”

“Today we will hear from General Chance Saltzman, Chief of the Space Operations for the U.S. Space Force, he will provide insights on the strategic steaks of U.S.-China competition in space, explore how the Department of Defense is preparing a increasingly contested domain, and following General Saltzman we will have a panel of experts to further explore issues related to U.S.-China competition in space.”

Commissioner Cliff Sims: “The space race of the 20th century captured the imaginations and the ambitions of the American people. However before NASA’s Apollo 11 delivered one giant leap for mankind, the Soviet Union’s Sputnik-1 raised fears of the capabilities that could be unleashed by United States adversaries. The question today is, will the next Sputnik moment be made in China or will the United States once again lead the way in the new space race.”

“Now, as it was then, the country who wins this race towards the stars will likely also be the country who’s this centuries defining power here on Earth. During my tenure in the office of the director of national intelligence under the leadership of then [unintelligible] space was made a priority intelligence domain and space force was added as the eighteenth member of the U.S. intelligence community. That was just over four years ago.”

“Earlier this year I helped lead the transition of administrations inside one of our intelligence agencies and as I got up to speed on various challenges and opportunities, I was struck by the progress that the People’s Republic of China had made in some of the critical technologies that will define the future, including in space.”

“China has become a peer competitor, and in some areas the worlds leader, in key technologies where they were not on our level just a few short years ago. According to ODNI’s (Office of the Director of National Intelligence) annual threat assessment released last week, China has achieved world-class status in all but a few space technologies. This development has enormous geopolitical, economic, and military implications, which I look forward to discussing in today’s hearing. The United States, our government, our private industry, and our people, must have a sense of urgency to win the space race 2.0, but we should also have the confidence of knowing that we have won before and we are well positioned to win again.”

“The U.S remains the global leader in launch capabilities, our commercial space industry is the envy of the world, no other country is catching rockets with chopsticks so they can be sent back out into space again. The Trump administration has ambitious goals for the “Golden Dome” missle defense shield, who’s success will demand continued innovation in space-based assets. We’re going back to the Moon, and god willing we’ll be the first country to plant our on Mars. I look forward to the testimony from our witnesses as we seek to retain U.S. space superiority in the 21st century”

As the opening statements make clear, the hearing focused on how America can maintain dominance in space to sustain its hegemony. China’s rapid advancements in civilian and military space programs were framed as a challenge to U.S. leadership, with Kuiken and Sims highlighting China’s strategic and planned approach to innovation. However in line with the American view of a win-lose situation, over the more realistic win-win reality, a Cold War-era urgency to beat China was invoked. These ideas and framing were carried forward with almost all of the testimonies.

Additional members of the commission present but foregoing opening remarks were Reva Price, 2025 Chair of the Commission, Randall Schriver, 2025 Vice Chair of the Commission, Aaron Friedberg, Hal Brands, Leland Miller, and Jonathan Stivers. All eight members of the commission did put forward questions following testimonies.

Questioning Saltzman

As a representative of the U.S. military, General Saltzman’s testimony and questions were focused on the use of space for military assets. Key parts of Saltzman’s opening testimony highlighted that space was no longer the domain for the United States to solely dominate with the alleged fielding of space weapons. Highlighted too was the increase of Chinese satellites, with Saltzman stating:

“In the past ten years, China’s on-orbit capability has grown by approximately 620%. As of October 2024, China claimed more than 1015 satellites in active service, and they are fielding more every year. For example, in 2023, China accomplished 66 successful space launches, placing 217 payloads into orbit with more than half performing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. This brings the PLA to approximately 510 Earth-observing satellites with optical, multispectral, radar, and radio frequency sensors, vastly enhancing its ability to detect and track U.S. aircraft carriers, expeditionary forces, and air wings.”

“Similarly, China has launched 36 G60 communications satellites to low Earth orbit (LEO), providing global internet connectivity and extending their digital reach. This represents the first tranche of a proliferated LEO (pLEO) constellation that will grow to 648 satellites by the end of 2025 and to 14,000 satellites by 2030, allowing it to compete with Western commercial pLEO constellations.”

Saltzman would be concerned about China’s ability to monitor American military assets, specifically in the Pacific, as it removes the advantages of surprise maneuvers by U.S. forces, which are the most aggressive in the world.

Proliferated low Earth orbit satellite architectures have become a gold goose for U.S. space-based reconnaissance assets, allowing military satellites to hide with commercial ones. SpaceX has helped lead the way on this, hiding Starshield military satellites with its Starlink constellation, with both spacecraft appearing quite similar. The U.S. Space Force is likely worried that, following America’s example, China will do the same.

As part of U.S. Space Force operations, the force is considering ways to deny or disable Chinese spacecraft in orbit. Naturally as a response, China is looking into doing the same to America, concerning leaders like Saltzman that the U.S. could be denied intelligence or imagery over specific intelligence critical regions. A non-vague example Saltzman gave was:

“China is developing orbital “inspection and repair” satellites with the stated intention of performing on-orbit maintenance and cleaning space debris. In January 2022, we observed their ability to forcibly pull a derelict BeiDou navigation satellite out of position into to a graveyard orbit above GEO. These types of satellites are dual-use and can be counterspace weapons as well as on-orbit servicing tools. What matters is intent, but it’s clear that the notion that China has the ability to capture enemy satellites is not science fiction—it is proven reality.”

The test in question is Shijian-21, a satellite servicing platform designed to verify mitigation technologies for orbital debris. Technologies from Shijian-21 have evolved into Shijian-25, which is focused on in-space refueling technology. Both of the satellites demonstrate capabilities the U.S. doesn’t have, through either canceled missions or demonstrations years away. American officials are worried about this capability as China leading the way disrupts plans for the U.S. to remain the dominant and leading nation in every field, as part of its global hegemonic efforts.

Regarding how to regain the edge in space, and what the U.S. would consider the present problem, Saltzman suggests that American space policy is overly restrictive and outdated, claiming that weapons are already in space so there should be American ones up there too. No solid definition of a space weapon was put forward. Additionally, Saltzman claims that the U.S. Space Force has insufficient resources for its goal of securing space for America globally, whereas China is concerned with neighboring areas of the Pacific.

General Chance’s full written testimony is available here:

Following the General’s testimony, Kuiken’s first question regarded if China is treating space as it does the law of the sea. Saltzman believes that China is treating space the same as it does maritime laws, via opportunism for so-called aggressive behaviors. It is worth noting that China has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea while the U.S. hasn't, out of fear it may create a precedent for space resources.

Regarding a question from Sims on the current rate of innovation and progress followed by an additional from Brands on the possibility of China becoming the preeminent space power, Saltzman stated that China focuses on its terrestrial neighborhood, the western Pacific, to rapidly develop capabilities that no other nation has (Shijian-21/25). Chinese preeminence in space could be a possibility due to America’s global need for its space assets, the General suggested indirectly noting what the U.S. currently has to do to maintain its current geopolitical position.

Friedberg raised a question of who’s ahead in space following the prior question, Saltzman partly deflected saying there is more nuance in how to measure capabilities. But it was said that the U.S. is behind on so-called space weapons due to policy, requiring training to be limited to simulations.

On quantum satellites, Miller asked why is the U.S. behind, likely provoked by a recent Chinese-South African test that saw a message sent 12,900 kilometers. Saltzman stated it is a matter of cost and budgets for investments to test and deploy new technologies. It was added that the potential benefits of such technologies are unclear.

Miller also asked about reusable rockets with the dozen possibly debuting from China this year. The response was that costs to launch and deploy capabilities become cheaper with the utilization of economies of scale. Additionally, the higher flight rate of reusable rockets allows for a more frequent updating of satellite technologies used on orbit as large constellations are replenished.

Questioning Alkire, Curcio, Samson, Cavossa, Cox

In the second panel of the hearing, testimonies were taken from five commission-chosen experts on space and China. Those experts, mentioned at the beginning, were Brien Alkire, Blaine Curcio, Victoria Samson, David Cavossa, and Andrew Cox.

Brien Alkire, of the RAND Corporation, focused his testimony on China’s strategic orbital assets. Like General Saltzman, Alkire highlighted the Shijian-21 and Shijian-25 satellites along with the country’s mega-constellation plans. Additionally, he made the following assessment of commercial space efforts in China:

“China has expanded its launch industry and accelerated its launch pace. In 2022, China began construction on a new launch complex on Hainan Island and built sea platforms that support launch. China had around 70 launches in 2024, compared with 150 launches for the United States.” — “China is prioritizing a tactically responsive space launch capability that leverages several of its new mobile, solid-fuel launch vehicles for this capability, provided by a combination of China’s established space companies and newer companies.” — “SOEs China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation or their subsidiaries dominate China’s space industry. However, as mentioned, newer companies are also entering the market, and they are primarily focused on launching smaller payloads to LEO. Interestingly, GeeSpace, a subsidiary of China’s largest automaker Geely, is fielding a LEO constellation to provide navigation services with centimeter-level accuracy for Geely-manufactured autonomous vehicles,and this company represents a new entrant that may be able to provide position, navigation, and timing services to the PLA as an alternative to BeiDou.”

Alkire’s assessment, and to an extent the RAND Corporations, is a case of the pot calling the kettle black as, despite being ten years old, China’s space sector is still new and its commercial launch operators do not yet have large enough cash reserves to have the pleasure of choosing who to launch. In its early days, the U.S. commercial launch sector was the same.

In a breath of fresh air, so to say, Blaine Curcio’s testimony was focused on how China’s government drives its commercial space efforts. You may also recognize Curcio from The China Space Monitor newsletter. In his testimony, Curcio made the following assessments of what drives private space enterprises:

“I would characterize the Chinese commercial space industry as extremely vibrant, but in some ways also tenuous. It is vibrant because there have been multiple high-level government proclamations in support of commercial space over the past decade, giving provinces, cities, private VCs, and entrepreneurs support to establish commercial space firms.” — “The Central Government also plays a guiding role, publishing nebulous announcements about their support for space. This includes Satellite Internet being included in the National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) list of New Infrastructures, multilateral agreements specifying space cooperation (i.e. “A New Era of China-Africa Cooperation” from November 2021 mentioning space projects), and vague pronouncements about opening up of relatively closed industries (i.e. the 2023 publication by MIIT of the “Opinions on Innovating the Management of Information and Communication Industry to Optimize the Business Environment”, which called for orderly opening up of the satellite internet industry).”

Regarding Chinese space industry talent, Curcio stated that the industry has undergone a significant transformation in recent years, driven by the rapid rise of commercial space companies that have reshaped talent dynamics. Traditionally, engineers and researchers had limited career options beyond state-owned enterprises like the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, but the emergence of private firms has created a competitive job market where top talent is increasingly drawn by higher salaries and career flexibility. With the increasing mobility and commercialization of expertise, accelerating innovation and fostering competition are gradually reshaping China’s space sector from a rigid, state-driven model to a more dynamic and market-oriented ecosystem.

On the potential for a possible Chinese version of SpaceX, Curcio asserts that:

“SOEs remain a very powerful force in the sector, which can hinder commercial development. Today there is still no “Chinese version of SpaceX”, i.e. there is no commercial firm trying to build very big reusable rockets. This is because, the bigger the rocket, the more directly firms are competing with SOEs, and the more directly firms are competing with SOEs, the more political hot water they could find themselves in. Bigger picture, the state still exercises a lot of control over what commercial space companies can and cannot do, which makes it hard for companies to confidently articulate their value proposition.”

In a continued breath of fresh air, and in my area of university studies too, Victoria Samson’s testimony was regarding China’s space diplomacy efforts, specifically between China and the United Nations, the Global South, and Russia.

Samson highlighted that at international forums, developing countries have tended to side with China, specifically around space weapons. This is due to, Samson asserts, China and Russia sponsoring a draft treaty preventing the placement of weapons in space while the U.S. opposes the effort at the United Nations General Assembly without proposing an alternative. Regarding the weaponization of space, it was added that:

“Space security is not just about defending assets but also about ensuring sustainable access and fostering international cooperation to prevent an arms race in orbit.”

Concerning China-U.S. space engagement, Samson highlighted that the Wolf Amendment, in place since 2011, has prevented the two sides from engaging due to the need to involve U.S. intelligence agencies prior to any meeting. As a result, obscuring China’s space progress to the United States instead of the intended opposite effect. To have the two space powers re-engage with each other, Samson suggests:

“One real avenue for constructive space engagement between the United States and China is based on the reality that the United States and China will be the main lunar superpowers, and there are significant opportunities for constructive space engagement with China on overlapping challenges. One near-term challenge relates to lunar radiocommunications for position, navigation and timing (PNT).” — “PNT signals are necessary for the United States’ lunar orbital and surface operations. They are fundamental for orbiting, landing, and surface operations. Avoiding signal interference between users of the spectrum used by PNT is critical, so engagement with China to avoid our interference with their signals is tied to the mission assurance of these missions. Likewise, China is keenly interested in their own lunar missions avoiding harmful radio interference. Additionally, PNT signals require standard time models to operate successfully, and are likewise assisted by a standard gravity model of the Moon.”

Additionally with the rise of mega-constellations in recent years, Samson recommends that improved coordination and information-sharing between Chinese and U.S. satellite operators, as well as other space stakeholders, is essential. As China deploys its constellations and operates in similar orbits, the potential for collisions is increasing, making bilateral communication on operational safety a priority. While U.S. operators and those from partner countries have established coordination and transparency practices among themselves, engagement with Chinese operators remains limited. Strengthening dialogue and formalizing norms for space safety could help mitigate risks and enhance overall space sustainability.

To end her testimony, Samson highlights that the use of “warfighting domain” to refer to space has handed U.S. adversaries an easy propaganda win with a simple and solid claim that America is preparing to fight wars in space. Referring to space as an “operation domain” would instead ease tensions in orbit while not limiting U.S. efforts, Samson suggests.

David Cavossa’s testimony was representative of U.S. commercial space companies and was the shortest of the five. As such Cavossa argued for the utilization of the private sector to drive innovation.

Cavossa begins his testimony by stating that China will catch up using a so-called unfair playing field, claiming that the nation has no regulatory oversight on its budgets with sectors it wants to fund. In reality, the Ministry of Finance (中华人民共和国财政部) and its many various departments manage the budgets. Additionally, Cavossa claims that China has no regard for space safety, public safety, or intellectual property. However, China has a regulatory framework that is being continually improved regarding space launches and orbital objects.

Regarding China’s progress in its commercial space sector in recent years, Cavossa shared:

“In just ten years, China has made tremendous progress in growing its non-government space capabilities, particularly in areas currently dominated by U.S. industry – launch and satellite manufacturing. In 2024, 145 orbital launches originated from the United States. China was second in the world at 68 launches atempts. There are now multiple non-government space launch enterprises in China, with six new reusable rockets planned for maiden launches in 2025. China has also made significant investments in launch infrastructure, including the construction of two new launch pads over just two years.”

“On the satellite side, China is accelerating build out of two LEO satellite broadband constellations. China has constructed at least seven new manufacturing facilities in recent years, with the capability to produce thousands of satellites annually. China’s national and provincial governments continue to pass regulatory plans and orders intended to accelerate development of a LEO satellite and launch systems. By the end of 2024, China’s filings at the International Telecommunications Union indicate plans for more than 156,800 satellites. Here, China’s goal is objective and clear: to connect every unserved and underserved community across the world with state owned, state censored internet from space ahead of the U.S., just as they have on Earth with Huawei and ZTE.”

It is worth noting that Cavossa’s statements likely reflected that of the U.S. space industry, who do not want to compete with China after failing to stunt the country’s launch sector after placing satellites under weapons exports among other legislation.

Andrew Cox’s testimony continued much of what Alkire said regarding military space efforts and the claimed use of commercial enterprises to do so, with more of the pot calling the kettle black. Cox claims that a so-called fusion of government and commercial goals is different from the U.S. government supporting, materially and financially, its space industry, which too share goals.

In order to support the commercial space sector, Cox highlights that many provinces have subsidized the creation of space technology hubs for manufacturing and assembly, directed by higher government policy. Subsidizing new industries is a no-brainer for developing new drivers of economic growth, something the U.S. used to do before the financialization of the economy won out. Cox does point out that innovation can move through the Chinese government quicker due to it being a one-party state with a set ideology, rather than being a two-party state stuck in ideological deadlock over the future.

Cox also expects Chinese companies to expand to global markets once they’re on stable footing, stating:

“The strategy played by Huawei is most likely going to be employed by China space companies as well. They will first expand into Southeast Asia markets where space coverage is easier, and the regulatory environment is in their favor. They will undercut the price and outpace the expansion of Western companies and offer additional incentives like funded schools and highways to sweeten the deal. Finally, they will slowly expand along the BIR to Africa, the Middle East, and South America”

All five’s full written testimonies are available here:

One of the first questions put forward regarded alleged intellectual property (IP) theft. Cavossa stated that Chinese companies are quick to copy innovations as if it ain’t broke don't fix it (like the industrial technology theft that kickstarted the American industrial base). Cox then asserted that KUKA robotics had its IP transferred to China for use in areas like spacecraft and satellite manufacturing, the company was bought for 4.5 billion Euros in 2016 by the privately-founded Midea Group.

In a question on whether the U.S. should pull out from various international space agreements, Samson argued against it as it would create a strong opening along with signaling that the U.S. is an unreliable power. It was highlighted by Samson that the Artemis Accords have more signatories than the International Lunar Research Station, despite one being a policy framework and the other being a collaborative program. Curcio added that in the last year, China has signed several agreements, specifically for its international mega-constellations and the Tiangong Space Station.

Samson was asked specifically on why the Wolf Amendment should be revised. In response, she argued that the two operators of vast satellite fleets should have a dialogue between the two to coordinate orbital changes to prevent collisions along with highlighting that the U.S. and China are the only two leading civilian space program powers and don’t communicate.

Regarding who the U.S. should try and engage should a dialogue open up, Samson suggested scientific enterprises for a swap of scientific data. Curcio suggested the major constellation operators instead as they are commercial entities.

For a U.S. strategy to better compete with China, Cox and Alkire recommend more resilient proliferated architectures for space assets. Samson suggested a debris removal program not affiliated with the military to compete on optics. Meanwhile, Curcio suggested bringing the rest of the U.S. industry on par with SpaceX and Starlink, as China’s commercial space companies are on par with each other while their U.S. counterparts aren’t.

In response to a question regarding critical space minerals, Samson pointed out that the United Nations Outer Space Treaty doesn’t say much about minerals other than you cannot appropriate space resources. Highlighted was the U.S. law and a Chinese proposal both say that you can so long as there is government oversight of a commercial actor.

In a question regarding who’s buying commercial launches and satellites in China, Curcio highlighted that most payloads remain Chinese or Chinese-built with a few international customers while satellite operators sell to government agencies, both national and regional among other customers.

Why was this hearing held?

The United States under the current administration would like to have a narrative that it is doing something regarding policy to compete with China rather than being a paper tiger at the whims of a few ultra-wealthy individuals. Despite being the world’s largest economy, the country does not do long-term economic planning, best illustrated by the “Liberation Day” tariffs.

Due to this, suggestions remain stuck on utilizing the free market more and utilizing narratives to maintain a high ground. This works well until you no longer have a research or industrial base.

The hearing also helps to forge narratives, specifically with some commission members trying to get General Saltzman to say that China is the preeminent space power, this would no doubt massively increase defense industry spending (where several members of the commission were prior). This is also why only one expert was from an organization dedicated to the peaceful use of space.

To bring an end to this unusually long article, I would like to leave you with part of an essay by President Xi Jinping (习近平) on scientific and technological innovation, I will leave the comparison of rhetoric up to you:

“[We] should deeply practice the concept of building a community with a shared future for mankind and promote open cooperation in science and technology. Scientific and technological progress is a global and contemporary issue, and only open cooperation is the right path. The more complex the international environment, the more we must open our hearts, open our doors, coordinate openness and security, and achieve self-reliance and self-reliance in open cooperation.”

“It is necessary to deeply implement the international scientific and technological cooperation initiative, broaden the channels of government and people-to-people exchanges and cooperation, give full play to the role of the platform for the joint construction of the "Belt and Road", take the lead in organizing international big scientific plans and big scientific projects, and support the joint research of scientific researchers from all countries. We must actively integrate into the global innovation network, deeply participate in global science and technology governance, work with all countries in the world to create an open, fair, just and non-discriminatory international scientific and technological development environment, and jointly address global challenges such as climate change, food security and energy security, so that science and technology can better benefit mankind.”

If there are any problems with this translation please reach out and correct me.

All images in this article, except the header, were screengrabbed from the senate live stream, I apologize for the poor quality due to the limited bit rate stream.

Gen. B. Chance Saltzman is the Chief of Space Operations, United States Space Force. As Chief, he serves as the senior uniformed Space Force officer responsible for the organization, training and equipping of all organic and assigned space forces serving in the United States and overseas. As members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Chief of Space Operations and other service chiefs function as military advisers to the Secretary of Defense, National Security Council, and the President. (Profile via U.S. Senate)

Blaine Curcio is Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting, a consulting and research firm focused on the Chinese space sector. Mr. Curcio is the preeminent expert on the Chinese space industry, having worked with Chinese and Western space companies on business development, international cooperation, and market analyses since 2010. His primary areas of focus include satellite communications, launch vehicles, space industrial base, and the intersection of space and large terrestrial markets. In addition to his role at Orbital Gateway Consulting, Mr Curcio is Senior Advisor at Novaspace, Publisher of the China Space Monitor Substack, and serves as the Young Executive on the Board of Directors of the Asia-Pacific Space Community Council (APSCC), an NGO based in Seoul, South Korea. (Profile via U.S. Senate)

Victoria Samson is the Chief Director, Space Security and Stability for the Secure World Foundation and has over twenty-five years of experience in military space and security issues. Ms. Samson is the head of the International Astronautical Federation’s Security Task Force and a member of the Space Security Working Group of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)’s Committee on International Security and Arms Control (CISAC). (Profile via U.S. Senate)

Dr. Brien Alkire is a Senior Operations Researcher at RAND and a Professor at the affiliated graduate school. His active areas of research are space warfighting technology and strategy, command and control, and artificial intelligence. (Profile via U.S. Senate)

Mr. Dave Cavossa is President of the Commercial Space Federation (CSF). Cavossa is a long-time space and satellite industry executive working at the intersection of commercial space, government affairs, and government services. (Profile via U.S. Senate)

Mr. Andrew Cox is the President of Fourspoke, LLC, providing consulting services in the areas of space, cyber, and command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence. (Profile via U.S. Senate)